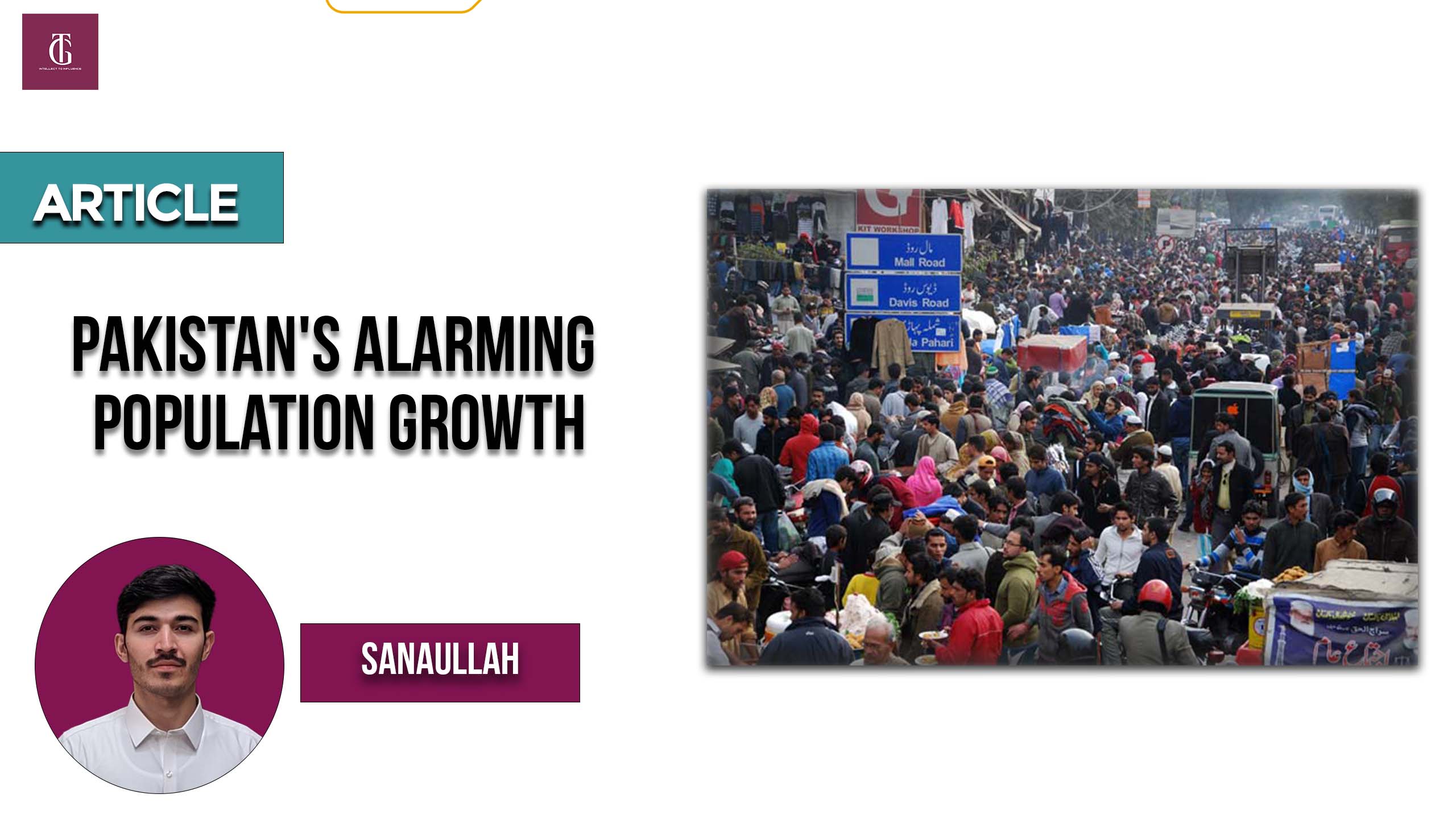

Pakistan’s intercensal population growth rate has been inexplicably high since 2017, according to preliminary results from the 2023 census. The demographic data for the nation paints an alarming picture. 3.6 children per woman is the estimated fertility rate, which hasn’t changed much in 15 years. In the meantime, different nations in South Asia are arriving at substitution fruitfulness levels (under two births for every lady), with populace development paces of one percent or less — subsequently putting Pakistan among the segment slow pokes of the district and perhaps the world.

The population’s behavior patterns and government policies in the country deserve serious reflection and discussion in light of these alarming statistics. All things considered, Pakistanis are not socially unlike the residents of Bangladesh or India — so there isn’t anything natural to make sense of the immense uniqueness in fruitful conduct. However, other nations’ policy responses to population growth differ significantly from ours.

Beginning during the 1960s, Pakistan put forth attempts to bring down fruitfulness to control populace development rates, however progressive ages of political precariousness hindered the cycle. It led five development plans relating to population projections and was one of the first countries in the region to announce a population program. However, the program was halted during the Ziaul Haq era (from 1977 to 1988).

The country was able to redouble its efforts despite the setback, and from 1991 to 1998, fertility rates dropped from six to four births per woman. During that time, democratic governments passionately advocated for family planning in public statements. Much past underwriting, programs were supported and institutional hardware activated to quantify the effect after some time by circling back to fruitfulness rates. Benazir Bhutto, the prime minister at the time, introduced the National Lady Health Worker Program for Family Planning and Primary Health Care at that time. It remains one of the world’s largest community-based programs to this day.

The alarming population statistics of Pakistan call for serious reflection and discussion.So why has Pakistan not had the option to bring down its populace development over the most recent 20 years?It is possible to make the case that the country’s policy structure, which is dominated by politicians, bureaucrats, power groups, and donors from abroad, deprioritized fertility decline over time.

Additionally, a significant portion of Pakistan’s current political leadership holds the belief that a larger population equals political and economic power. This goes against the worldwide evidence that shows that high rates of population growth hinder economic prosperity. Similar to Pakistan, Indonesia and India have faced similar financial and governance challenges, but they have worked around them to maintain population sizes that do not strain their economies. The distribution of resources, such as Pakistan’s National Finance Commission Award formula, which is heavily skewed in favor of population [82 percent], has not hampered their efforts either. This underscores the need for additional resources to accommodate the growing population.

In contrast to other nations, Pakistan has struggled to implement structural and strategic governance and structural reforms, such as rewarding provinces for reducing population growth rates. Bureaucrats had a hard time adapting to the new administrative landscape that resulted from the passage of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution in 2010. This amendment gave provinces autonomy over policy areas such as population welfare and health. The step controlled the national government’s capacity to foster a drawn out vision and plans, and finished in equivocalness between the bureaucratic and common states in regards to assets and obligation. The crucial issue of balancing population growth with Pakistan’s resources and development priorities was omitted in the midst of this lack of clarity.

The needs of women’s reproductive health, particularly fertility and family planning, have not been the primary focus of the donor agencies’ discourse, despite the fact that these issues—maternal mortality, malnutrition, and early childhood development—are the primary topics of discussion.

So, how can we get out of this bind?

In order for Pakistan to have sufficient resources to meet the needs of its population, policies that reduce fertility rates must be designed and implemented by exceptional leadership. In addition, in order to guarantee a shared vision regarding population growth that takes into account the diverse requirements and dynamics of the population, it is necessary to achieve consensus among the most important stakeholders in the nation.

Populace government assistance ought not be decreased to language. It should be embraced as a strategy instrument to guarantee the prosperity of each and every person, particularly weak gatherings like ladies and youngsters. Millions of families with undernourished and out-of-school children require access to health care. It will need to target millions of women who have unwanted pregnancies and issues during childbirth.

In order to improve the shameful state of women’s health, the federal and provincial governments must both increase fiscal space and invest in structural reforms. The Council of Common Interests mandated Population Fund in 2018 to finance expanded coverage for family planning has not been put into action. By rewarding provincial health programs and private-sector providers for providing easily accessible and effective reproductive health services, the Fund should be quickly utilized to meet the unmet demand for family planning services.

While givers can uphold government endeavors, by exhibiting inventive arrangements, they can’t without any help finance effective enormous scope programs. As a consequence of this, it is necessary for governments to take the initiative in putting plans into action that are intended to make the innovations last beyond the assistance of donors.

At last, mediations pointed toward diminishing populace development must find success if the public authority initiative at the most elevated level screens them. The state leader’s key guide, which manages appropriate arrangement matters like the economy and energy, should likewise give due significance to lessening fruitfulness rates.

Pakistan has received praise for managing the Covid-19 pandemic successfully and nearly eliminating polio when federal and provincial governments shared responsibility. A similar methodology ought to be utilized to meet the crucial privileges of our 240 million or more residents to essential conceptive wellbeing data and administrations. There is a golden chance for this government and the next to right this wrong. The trial of administration lies in whether they will respond to the call.

SANA ULLAH

Sanaullah is a passionate and dedicated student currently pursuing a degree in Political Science at Quaid-e-Azam University in Islamabad. As he embarks on his fourth semester, he is driven by a strong desire to understand the intricacies of politics, governance, and their impact on society.