South Asia stands at a critical juncture, grappling with a multitude of challenges that hinder its progress and potential. Three prominent factors contribute to the complexities faced by the region. Foremost among them is the long-standing and highly significant Kashmir dispute. Both Pakistan and India recognize the complexity of the Kashmir dispute, understanding that progress in other areas cannot be achieved without resolving it first.

The Pakistani mindset is deeply entrenched in the Kashmir issue, making it a major obstacle to improving relations with India. On the other hand, India uses the Kashmir argument for their advantage, invoking acts of terrorism and forcing Pakistan to defend its position. This ongoing debate has impeded a rational evaluation and hindered progress between the two neighboring South Asian countries, leading to a state of neither peace nor war.

It is astonishing but true that in this modern century, a time characterized by connectivity, mutually beneficial coexistence, and interdependence among modern economies, South Asia remains the least connected region in the world. Trade between the eight member countries accounts for only two percent of their combined global trade.

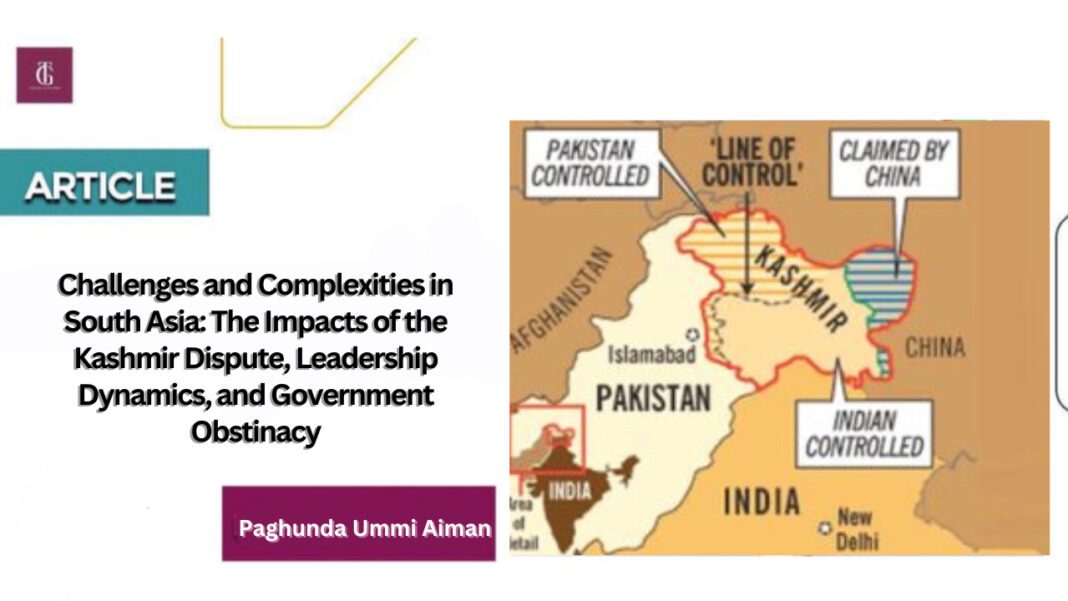

India believes that it has addressed the Kashmir issue by making amendments to its Constitution and revoking clauses that granted special status to the region. However, Pakistan disagrees with this unilateral legislative action, as they view the Kashmir dispute as a bilateral matter that remains unresolved. Furthermore, both India and Pakistan are signatories to the United Nations’ list of recognized disputes, which includes Kashmir.

Despite the existence of numerous resolutions on Kashmir, India has managed to thwart their implementation, defying the international consensus that recognizes Kashmir as a global flashpoint. Over time, the significance and impact of the issue have diminished due to Indian stubbornness and the failure of both sides to create favorable conditions for its resolution.

In 2019, India altered the nature of the Kashmir issue, catching Pakistan off guard, despite Pakistan relying on the disputed status of Kashmir. Strategically, Pakistan appears to be struggling to find an appropriate response, while their options seem limited due to the tacit approval of the international community, which has chosen to ignore the matter. India considers the issue resolved, but for Pakistan, it remains a challenge as they grapple with this paradigm shift. Practically speaking, Pakistan’s options are constrained to political and diplomatic avenues. If the status quo persists, there may be an irreversible change in the paradigm

The second factor is the nature of the Modi government, which hinders any potential for improvement. With a firmly established autocratic rule and control over various aspects of the state and society, Modi effectively utilizes these levers to serve his political agenda. Domestically, this translates into a disturbing agenda of marginalizing individuals who do not adhere to the Hindu faith, which accounts for approximately twenty percent of the 1.4 billion population.

He also frames Pakistan as a constant threat, exploiting it as a political tactic to secure electoral victories. Prior to each election, he often orchestrates border skirmishes and uses them to create a narrative of fabricated success. With another election approaching in 2024, where Modi aims for his third consecutive term, the region anxiously awaits what actions will be taken.

These actions are likely to further obstruct any potential for fresh perspectives in South Asia, preventing a breakthrough from the current stalemate and enabling a mutually beneficial coexistence. The key question remains whether Modi can transcend his own ambitions and an inflated sense of personal and national grandeur. This factor alone will determine if the two nations can truly find common ground. The reasons behind Modi’s reluctance are equally revealing. After decades of India holding an advantage over Pakistan, the latter finds itself embroiled in political instability and economic turmoil.

Years of ineffective governance have led Pakistan to the brink of economic failure and societal despair. Given these circumstances, Modi and India consider it unwise to extend a helping hand to an old adversary. Enhanced trade between the two neighboring countries could significantly improve the lives of millions on both sides of the border. However, Modi seems more inclined to witness Pakistan’s downfall rather than promote mutual progress. This stance could have serious consequences for India and the region as a whole.

The potential reactions from Pakistan to such manipulative tactics remain uncertain, further heightening the fragility of the already delicate region. At present, both Modi and India seem to take pleasure in Pakistan’s misfortune. As per Modi’s sentiment, “Let Pakistan suffers the consequences of its own missteps.” Unfortunately, this situation rings true. The prospect of better times for South Asia hinges on the emergence of a true statesman within the region.

The third factor pertains to the stubbornness of government officials in both nations who have fueled fear and propagated rhetoric in pursuit of their agendas, which revolve around fostering anger, hatred, and racial exclusivity. They exploit foundational issues like Kashmir to perpetuate their cause, distorting the imperative for a fair resolution. The currency of hatred thrives as Indians develop aversion towards Pakistanis due to their religious identity as Muslims, while Pakistanis harbor resentment towards India for what they perceive as a cunning occupation of Kashmir.

Diplomats and military personnel have embraced this narrative and furthered their respective positions. However, if utilized more constructively, these individuals possess the capability to forge innovative solutions. Unfortunately, inertia and an unwavering adherence to their own historical experiences prevent them from pursuing such possibilities.

Unless these three challenges are confronted through widespread education, open debate, and mature interactions, they will continue to impede the progress of both nations. This is particularly crucial as regional stability hangs in the balance, with major powers competing for influence, either through direct engagement or by supporting proxies to advance their own agendas.

The vast population of approximately two billion people in the broader SAARC region remains trapped in the power dynamics of the two nuclear-armed nations, India and Pakistan. While they may be willing to engage in regional arrangements such as the SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organization) and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), they show little initiative to revive SAARC or foster a thriving economic region within South Asia. Consequently, poverty remains widespread on both sides. Africa, often regarded as lagging behind, may soon surpass South Asia as its people strive for a better future.

As the old order gradually crumbles, South Asia continues to be held back by an ineffective and financially depleted leadership. It is susceptible to becoming a pawn in the game of major powers seeking to enhance their influence through indirect means. Unfortunately, South Asia will always fall short, as demonstrated by Pakistan’s own experiences. The region deserves better, but its inherent potential remains largely unfulfilled under the pervasive shadow of the challenges that plague it.

Pakistan has much work to do in order to harness its potential and improve its socioeconomic foundations, while India must transcend its arrogance and perceived superiority to foster a sense of complementarity that can lead to a more promising future. Modi, if he secures a third term, will need a fresh approach and a new vision.