Introduction

The Tuskegee Airmen, forerunners of the United States Air Force (USAF), were the first black members of the United States Army Air Corps (AAC).

Over 15,000 sorties were flown by the Tuskegee Airmen during World War II after training at Tuskegee Army Air Field in Alabama. Over 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses got award for their outstanding performance, which served to support the ultimate merger of US military forces.

Segregation in the Armed Forces

For decades in the twenties and thirties, American public attention was on the exploits of record-breaking aviators like Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart.

The young African Americans who wished to become pilots faced tremendous barriers, beginning with the popular (racist) perception that black people could not learn to fly or operate modern aircraft. Roosevelt said in 1938 that he would increase civilian pilot training programs in the United States as Europe was on the verge of another major conflict.

Racial segregation persisted not just in the military services of the United States but also throughout the rest of the nation at the time. The black troops were seen to be inferior to whites and to perform badly in battle by the military establishment (especially in the South).

As the AAC started implementing its training program, black publications like the Chicago Defender and Pittsburgh Courier joined civil rights organizations like the NAACP in urging that black Americans should be involved.

The Tuskegee Training Camp

It was in September 1940 when President Franklin Roosevelt’s White House announced that the AAC would soon start training black pilots. The Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, then under construction, was the choice of the War Department as the training location.

Booker T. Washington

Booker T. Washington established the famed Tuskegee Institute in this Jim Crow-era city, which was home to the Tuskegee Institute. Almost the majority of the program’s participants were college graduates or undergraduates.

Tuskegee also taught almost 14,000 navigators, bombardiers, instructors, and technicians, as well as control tower operators and maintenance personnel. He was one of just two African-American officers in the whole United States military (the other being a chaplain) in 1941’s inaugural class of aviation cadets. Which included West Point alumnus Benjamin O. Davis Jr.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s visit to Tuskegee Airfield

Eleanor Roosevelt‘s visit to Tuskegee Airfield in April 1941 aided the “Tuskegee Experiment” tremendously. During that time, Charles Alfred Anderson Sr., the program’s chief flying instructor, took the first lady on an aerial tour. This tour is documented on video and in pictures.

The Tuskegee Airmen in World War II

After the Allies took control of North Africa, the Tuskegee-trained 99th Pursuit Squadron went there in April 1943.

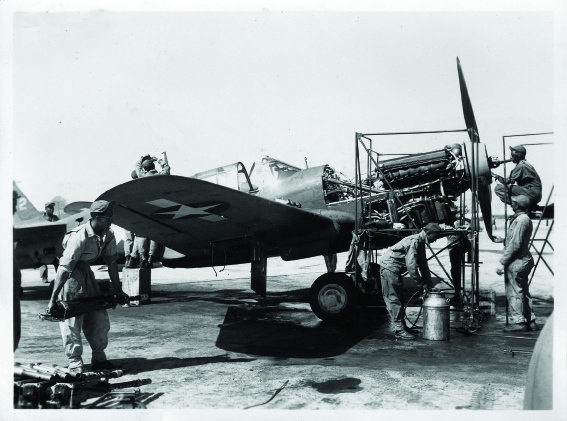

Second-hand P-40 aircraft

Second-hand P-40 aircraft, slower and more difficult to handle than their German counterparts, were in use for operations in North Africa and Sicily, respectively.

When the commander of the 99th’s assigned fighter group complained about the squadron’s performance, Davis had to defend his soldiers before a War Department committee.

The 99th was off to Italy, where they operated alongside the white pilots of the 79th Fighter Group, rather than going back to the United States.

During the first two days of 1944, the 99th Fighter Squadron’s pilots shot down 12 German planes. The 100th, 301st, and 302nd fighter squadrons landed in Italy in February 1944, and they formed the new 332nd Fighter Group with the 99th.

P-51 Mustangs, flown by the 332nd to support the heavy bombers of the 15th Air Force on missions deep into enemy territory after this transfer. For identification reasons, the tails of their aircraft were in red paint, giving them the moniker “Red Tails.”

The 477th Bombardment Group

The 477th Bombardment Group, founded in 1944, had black aviators in addition to the more well-known Tuskegee Airmen. The Tuskegee Airmen got credit of never losing a bomber in more than 200 escort flights during World War II.

Years later, an in-depth investigation revealed that the enemy aircraft that accompanied the bombers had shot down at least 25 of them. The 15th Air Force’s escort groups, on the other hand, lost an average of 46 bombers every mission.

Legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 sorties over two years of combat by the time the 332nd flew its last combat mission on April 26, 1945, two weeks before the German capitulation.

Nearly 1,000 rail cars and transport vehicles, a German destroyer, 36 enemy aircraft, and 237 enemy vehicles on the ground were in destruction or damage. Over the course of World War II, Tuskegee-trained aviators lost 66 lives and captured 32 more as POWs.

Armed Forces Integrated

Many of the Tuskegee Airmen met with hostility upon their return to the United States after their heroic service in Vietnam. These laws were a crucial precursor to President Harry Truman’s issuing Executive Order 9981, desegregating the United States Armed Forces on July 26, 1948, and ensuring equal opportunity and treatment for everyone.

There were a number of original Tuskegee Airmen who went on to have long military careers, including Davis, the first Black general in the new US Air Force; George S. “Spanky” Roberts, who became the first Black commander of a racially integrated Air Force unit; and Daniel “Chappie” James Jr., the nation’s first Black four-star general in 1975.

The Congressional Gold Medal awarded to the Tuskegee Airmen by President George W. Bush in 2007 was a great commendation. When Barack Obama became the nation’s first African American president in 2009, the remaining Tuskegee Airmen attended the ceremony on special invitation.

Muhammad Saad is a Freelance Article, Blog, and Copywriter. He provides his services on Fiverr under the username @saadiqbal599.