History and migration

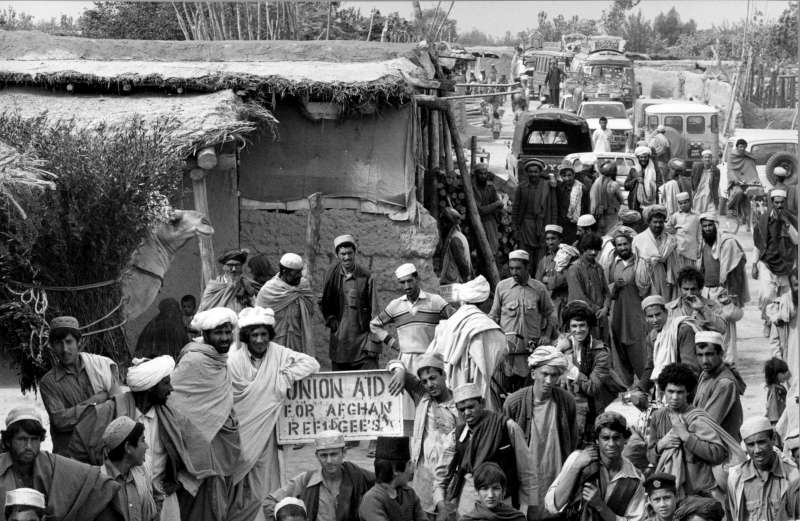

In 1979 the first wave of Afghan refugees in Pakistan started. During the Soviet-Afghan War, a large number of Afghans fled their nation. Thousands more followed, fleeing “tough, if not impossible” conditions. Including the danger of mass arrests, killings, assaults on public meetings, the destruction of Afghan infrastructure, and the targeting of Afghanistan’s agricultural and industrial sectors.

Sheltering Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

Throughout the decade, there were three million Afghan refugees in Pakistan and around two million in Iran. However, other estimates suggest that by 1990, Pakistan was home to almost 4.5 million undocumented Afghan refugees.

With assistance from the UNHCR and primary funding from the United States government. Pakistan continued to welcome and facilitate the integration of these Afghan refugees.

Approximately 3,3 million Afghan refugees were sheltered in 340 refugee camps along the Afghan-Pakistan border in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa towards the end of 1988. (KP).

In November 1988, The New York Times claimed that around 100,000 refugees resided in Peshawar and more than two million lived in KP (known as the North-West Frontier Province at the time). The Jalozai camp, located on the outskirts of Peshawar, was one of the biggest refugee camps in the NWFP.

Despite the fact that, by migrating, many Afghan refugees averted extreme bloodshed. They were nevertheless vulnerable to political injustice and discrimination at the hands of Pakistan, their host nation. In Pakistan, perceptions and sentiments regarding Afghan refugees saw a significant shift in the decade that followed.

Pakistan’s Reliance on the U.S. Support

Despite the fact that the country first welcomed these migrants, adopting “terms from Islamic discourse to justify receiving these refugees in their moment of need.” It rapidly turned on its subjects and began to blame them for a number of problems.

That plagued the country for the next three decades (until their eventual repatriation from 2001 to 2009), including terrorism, unemployment, disease, and various conflicts.

This might be attributed in part to Pakistan’s reliance on U.S. support. Which increased from about $160 million in 1984 to almost $630 million in 1987. This funding may have convinced Pakistan to house Afghan refugees as opposed to focusing on humanitarian concerns.

As a consequence, Afghan refugees were subject to a variety of inequities, including a lack of political representation. Afghan migrants were forced to register with one of seven Islamic parties pre-approved by the Pakistani government in order to relocate to Pakistan.

In doing so, the Pakistani authorities aimed to thwart the formation of a single organization on behalf of Afghan refugees. Therefore, preventing the “Palestinianization” of Pakistan. As a consequence, Afghan migrant voices were mostly repressed.

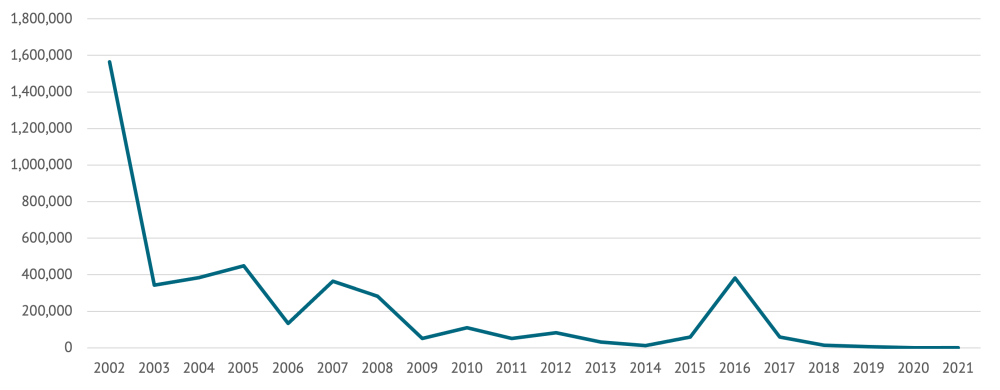

Refugees voluntarily returning to Afghanistan

This “extreme” language reappeared after September 11 as proof of the last change in Pakistan’s stance toward Afghan migrants. Prior to September 11, 2001, the Pakistani government had ceased distributing food rations to refugee settlements.

However, as a result of the World Trade Center attacks and the accompanying worldwide emphasis on Afghanistan. Pakistan chose to work toward the total return of Afghan refugees. With the assistance of the UNHCR, Pakistan started to support the “voluntary return” of these refugees.

Approximately 1.52 million refugees were “voluntarily returned” by Pakistan between March and December of 2002. And an additional 5 million over the next six years.

Nonetheless, there is considerable evidence to imply that these repatriations were not as “voluntary” as stated, as a joint study from the UNHCR and Pakistan indicated that 82% of refugees did not desire to return home.

Regardless, millions of refugees were later deported and returned to a nation where they had little to no capacity to make a living, which was worsened by the shortage of resources compared to the number of refugees being deported.

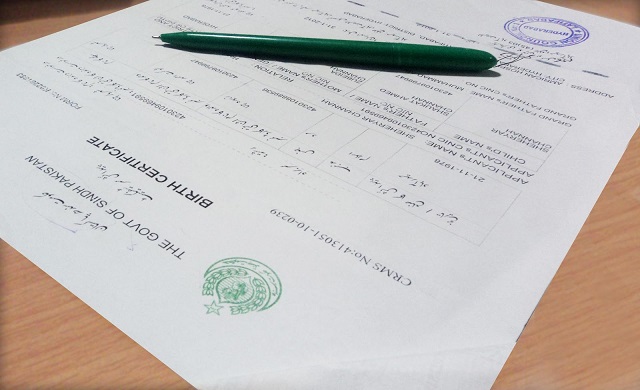

Pakistan Issues Identity Cards to Afghan Refugees

Pakistan has concluded a months-long campaign to register Afghan refugees and issue them identity cards that will protect and safeguard their interests.

Campaign Supported by the U.N

The government-run campaign, supported by the U.N. refugee agency, began in mid-April. The registration drive has updated the data of some 1.4 million Afghan refugees. This is the first large-scale effort to verify the status of refugees in Pakistan in the last 10 years.

UNHCR spokesman Babar Baloch

UNHCR spokesman Babar Baloch says the refugees are given so-called smart identity cards. Which legitimizes their status and facilitates their access to humanitarian aid and other benefits.

“The new identity cards are an essential protection tool for Afghan refugees and give them faster and safer access to health and education facilities and to financial services as well.”

“This drive also provided an opportunity for Afghan refugees to flag any specific protection needs for vulnerabilities.”

The Taliban in Afghanistan

The UNHCR reports that more than 300,000 Afghans have fled to Pakistan since the Taliban took over their country in August. Their situation is precarious as most have entered the country illegally and may be liable for deportation.

The United Nations warns Afghanistan is becoming one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. It notes that 24.4 million people, more than half of the population, need life-saving humanitarian assistance.

It says more than 9 million Afghans are displaced within the country, with little prospect of returning soon to the homes they fled.

Hostile Attitude Towards Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

The strong social cohesion that had existed in the past between Afghans and their Pakistani hosts “was deteriorating.” The Pakistani administrations before Imran Khan contributed to this situation by developing a narrative that associated Afghan migrants with terrorism and economic difficulties in Pakistan.

As Afghans were wrongly accused of the December 2014 assault on the Peshawar Public Army School, hatred grew. According to the Pakistani community, “they have acquired a negative attitude towards the presence of Afghans.”

Coexistence Under Tension

In comparison, a formal poll done with Afghans in Pakistan and focusing on current dynamics showed that 82 percent of respondents felt welcomed by others, including Pakistani residents, in their area of residence, while just 4 percent felt rejected by the host society.

The remaining respondents (14%) had experienced both conditions. These findings “indicate a reasonably high level of social cohesiveness among Afghani and Pakistani people.” Traditionally, “social cohesiveness between Afghans and the host community has been good,” but relations have shifted from support to “coexistence under tension” with the possibility of violent escalation.

The Socio-Economic Situation of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

Education

The 2018 Global Monitoring of Education Report suggested that the availability of education for Afghan refugees must be considered in light of Pakistan’s “very poor” educational system.

According to the 2019-20 Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey (PSLM), 32% of children live in poverty. The majority of Pakistani youngsters aged 5 to 16 do not attend school.

According to Education Cannot Wait (ECW), the UN’s global fund for education in catastrophes and extended crises, as of December 2021, there were a total of 22.8 million children who were not attending school, the second-highest number globally.

In December 2012, legislation went into effect granting every kid, regardless of gender, country, or ethnicity, the fundamental right to free and mandatory learning in their local public school. For the purposes of school admission, a child’s age will be determined using the Form-B of NADRA and a birth certificate obtained in accordance with the regulations; however that almost no child shall be refused school entry for lack of documentation of age.

Employment

The economy of Pakistan is mostly unorganized and unreported. According to the source, Afghans in Pakistan are also ineligible for public sector jobs due to their legal status.

UNHCR claimed that a Computerised National Identity Card (CNIC) was a “necessary precondition for accessing career opportunities in the official sector” and that refugees had “very limited access to the established job market.”

While “many refugees were found to be talented and self-employed,” there were no Afghan refugees working in the official economy (public or private sector) due to the lack of a national identity card.

While unskilled or low-skilled Afghan immigrants are employed in the “transportation business (without driver’s licenses), as tailors, junk collectors, and shopkeepers.” They also raise and trade animals, serve as security guards, washermen, and waiters,’ operate mobile food stalls or tandoors (bakeries) or mobile repair shops, and are employed in mines or industrial plants around Pakistan.

Access of documents to Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

Hospitals, the NADRA, and local governments (Union Councils) can issue birth certificates. Children born in hospitals are automatically issued birth certificates regardless of nationality. In addition, “there is no central database and no automatic registration mechanism for the numerous infants delivered outside of hospitals.” Despite the fact that birth registration is theoretically required, many births in the nation (including those of Afghan children) are not registered.

In the past, the Pakistani media reported that Afghan migrants received computerized national identity cards (CNICs) through unofficial channels.

The head of the NADRA revealed that some Afghan nationals got CNICs by pretending to be Pakistani residents’ relatives. The NADRA has canceled these cards. However, in January 2021, Pakistan’s interior minister said that up to 200,000 CNICs had been revoked because Afghan residents had gained them through illegal ways, such as providing fraudulent birth certificates.

Being prohibited from possessing SIM cards, Afghans without Proof of Resident cards have reportedly sought alternative solutions, such as obtaining a SIM card in the name of another person, borrowing mobile phones from a friend, or using SIM cards issued by mobile operators based in Afghanistan.

Registration Drive for Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

There are 40 verification sites that were set up across Pakistan during the registration drive last year. The mobile registration vans sought out Afghan refugees living in remote areas.

A mass information campaign was also carried out to explain the purpose of the campaign to Afghan refugees. This effort has paid off with large numbers participating said Baloch.

“Among them, there were 200,000 children under the age of five who were registered by their refugee parents,” Baloch said. “More than 700,000 new smart identity cards have also been issued to date. The remaining cards will be printed and distributed in early 2022. These cards are valid until 30th of June 2023.”

Baloch says the campaign is part of a wider effort to assist and protect Afghan refugees. Gathering more detailed information about the refugees, he says will enable the government and aid agencies to better tailor assistance to them.

In addition, he says it will facilitate support for those refugees who decide to return home when conditions in Afghanistan allow.

| Overview of extensions of the validity of Proof of Residency (PoR) cards |

| PoR cards originally issued in 2006–2007 | PoR cards are valid until December 2009 |

| March 2010 | PoR cards are valid until 31 December 2012 |

| December 2012 | Six-months extension given until 31 June 2013 |

| July 2013 | PoR cards are extended until 31 December 2015 |

| January 2016 | Six-month extension until 30 June 2016 |

| June 2016 | Six-month extension until 31 December 2016 |

| September 2016 | Three-month extension until 31 March 2017 |

| February 2017 | Nine-month extension 31 December 2017 |

| 3 January 2018 | One-month extension until 31 January 2018 |

| 31 January 2018 | Two-month extension until March 2018 |

| March 2018 | Three-month extension until 30 June 2018 |

| 30 June 2018 | Three-month extension until September 2018 |

| October 2018 | PoR cards are extended until 30 June 2019 |

| 27 June 2019 | PoR cards are extended until 30 June 2020 |

| 2021 (DRIVE exercise) | PoR smartcards are valid until 30 June 2023 |

literally amazing… more power to you. TimesGlo is really a great platform.. sea of knowledge...